Spread the word and join Strong Families member organizations and activists for this event providing resources and support to young parents!

In March 2012 the New York City Human Resources Administration's launched a highly offensive anti-teenage pregnancy campaign: “Think Being a Teen Parent Won’t Cost You?” Although the ads have mostly disappeared the shame and stigma teenage families endure everyday has not.

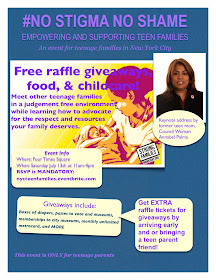

In response to the offensive ads several New York City based organizations and advocates have launched a counter campaign, "No Stigma No Shame," which is finding ways to counter damaging stereotypes and support young parents.

We are happy to announce that on Saturday July, 13 the No Stigma No Shame: Empowering and Supporting Teenage Families Conference will take place at Four Times Square from 11am-4pm.

This conference will create a judgment-free, supportive, and empowering environment for New York City teenage families and connect them with resources and programs that are teenage family-friendly. The keynote address will be made by former teen mom and distinguished Council Woman Annabel Palma whom represents the Bronx's 18th District.

The event will include information sessions on emotional wellness, sexual/reproductive health, education, and advocacy. Raffle prizes will include passes to New York City's museums and zoos, boxes of diapers and much more all while providing child care, and food!

This event is completely FREE and open to all teenage parents (male and female). RSVP is mandatory and can be completed here.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)